She has argued both that National Geographic denied competent scholars access and that the scholars who were granted access to the Codex Tchacos were not able to go about their work properly due to the constraints put upon them, accusations similar to those leveled at the guardians of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Turner Professor of Biblical Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Rice University) has published a book, The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says, questioning both the National Geographic's handling of the Gospel of Judas' publication and the veracity of its translation. (As a book the Tchacos Codex may be older than the twelve surviving codices of the Nag Hammadi Library.)Īpril D. The team also hopes to look at the cartonnage (a sort of paper-mâché used to stiffen the codex's cover) in order to find clues about who made the codex and when/where.

A critical edition of the Codex Tchacos, including complete, near life-sized color photographs of 26 pages, a revised transcription of the Coptic, and complete translation of the codex was published by National Geographic Society in 2007.

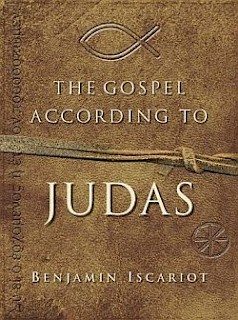

A special issue of National Geographic magazine was also devoted to the Gospel of Judas. The Society also created a two-hour television documentary, The Gospel of Judas, which aired worldwide on the National Geographic Channel on April 9, 2006. In April 2006, a complete translation of the text, with extensive footnotes, was released by the National Geographic Society: The Gospel Of Judas ( ISBN 1-4262-0042-0, April 2006). According to National Geographic's website, fragments purported to be from the codex may also be part of an Ohio antiquities dealer's estate. Roughly a dozen pages of the original manuscript, seen briefly by scholars in the 1970s, are missing from the Codex today it is believed that they were sold secretly to dealers, but none have come forward.

She named it in honor of her father, Dimaratos Tchacos.

(Archivists can do nothing to remedy this damage since it is caused by the outer layers of the papyrus flaking off-taking ink with them.) Scholars heard rumors of the text from the 1980s onward as dealers periodically offered it for sale (displaying portions of the text or photographs of portions of the text in the process.) It was not examined and translated until 2001 after its current owner, Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos, concerned with its deteriorating condition, transferred it to the Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art in Basel, Switzerland. One stored it in a safe deposit box and another actually froze the documents, causing a unique and difficult kind of decay that makes the papyrus appear sandblasted. The codex was rediscovered near El Minya, Egypt, during the 1970s (possibly 1978), and stored in a variety of unorthodox ways by various dealers who had little experience with antiquities.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)